Insetting is moving into the spotlight as corporates try to decarbonize their supply chains. Increasingly, companies are turning to set up carbon reduction or removal projects within their value chains in reaction to quality doubts associated with purchasing external carbon credits. While some experts have touted this approach as a promising climate solution, caution must be taken to prevent issues such as double-counting of benefits and replicating the quality challenges in the voluntary carbon market (VCM) with even less oversight.

Implementing emission-reducing initiatives into a company's supply chain is an important component of climate action as a valuable addition to beyond-supply chain mitigation activities. That said, it is currently far away from setting the right boundaries.

What is insetting?

The term “insetting” has been used to refer to a company’s efforts to prevent, reduce, or remove emissions within its own supply chain, but outside of its operational boundaries. This is as opposed to offsetting, which is when a company compensates its carbon footprint by paying for the removal or avoidance of emissions outside of its own supply chain. Still, the general mechanisms and methodologies used for insetting are often similar, if not identical, to those of established offset methodologies.

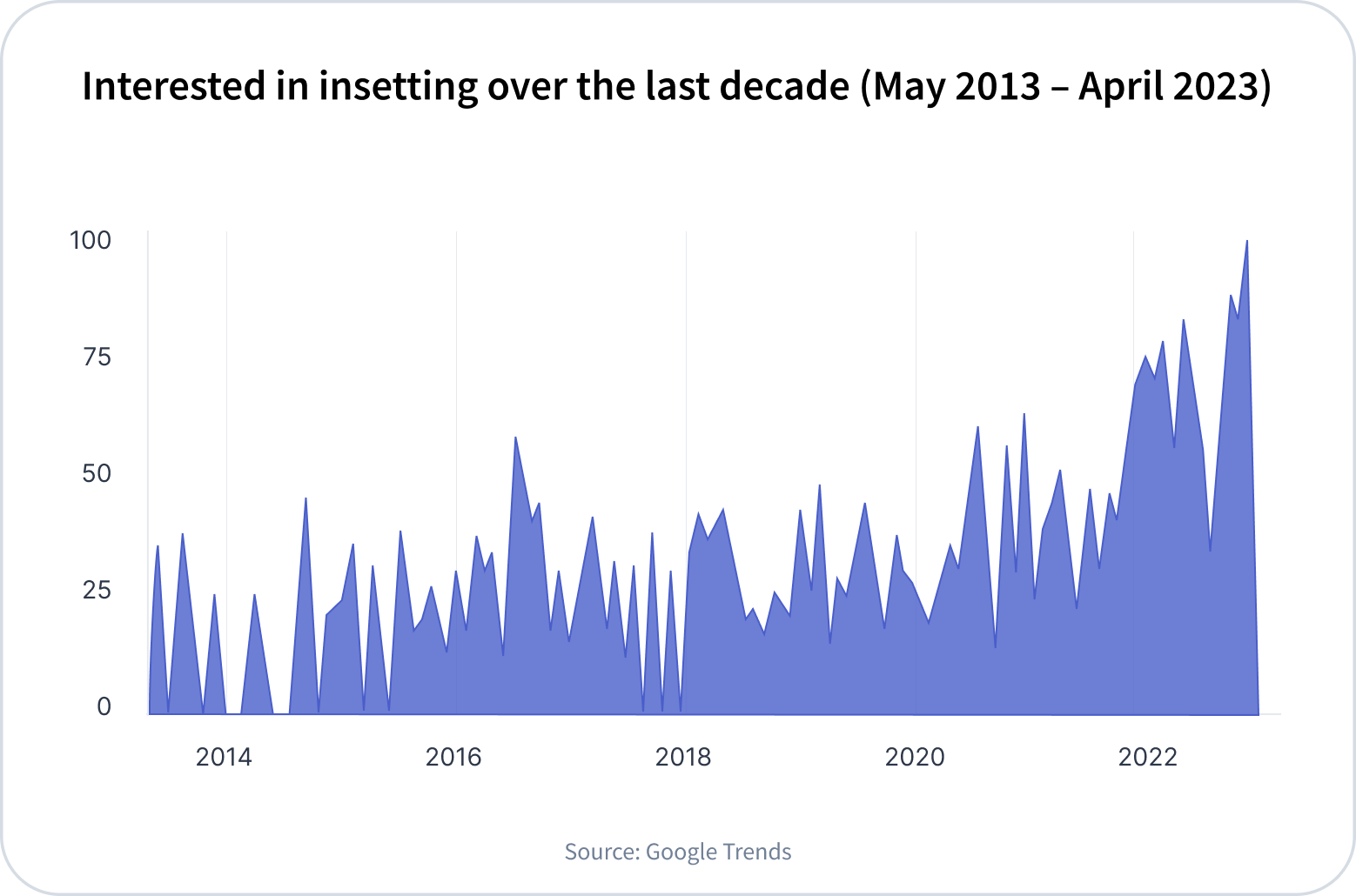

Insetting is by no means a new approach – it was coined and promoted by Plan Vivo (a carbon-crediting program) and PurProject (a developer of nature-based projects), about a decade ago. Judging from Google Trends and recent press coverage, however, insetting seems to gain more and more attention.

Guidance on insetting

There are multiple definitions for the term “insetting” in use, and there is no standardization in its use as of yet. Nevertheless, some initiatives have attempted to drive forward the discussion and develop standards.

In 2015, the International Carbon Reduction and Offset Alliance (ICROA) formulated three best practices in the use of insetting:

- To claim to be insetting and account for reduced or removed emissions accordingly, a company must invest financially in the development and maintenance of the insetting project. This project can be developed by the company, its suppliers, or third-party organizations.

- Investment projects must involve a supply-chain activity (i.e. involving the production or sourcing of raw materials, product transformation, or product transportation) and the supply chain community (all stakeholders with a direct link with the supply chain).

- Activities covered must generate additional, unique, measurable, and verifiable emissions reductions.

The International Platform for Insetting (IPI), initially established by Plan Vivo and PurProject, is the most prominent advocate body for insetting. In March 2022, IPI released its Practical Guide to Insetting, where insetting is defined as “interventions by a company in or along their value chain that are designed to generate GHG emissions reductions or carbon removals, and at the same time create positive impacts for communities, landscapes and ecosystems.”

Another key organization in corporate climate action, the Science Based Target initiative (SBTi), considers such insetting measures to be distinct from efforts to ‘neutralize’ or ‘compensate’, instead proposing that insetting measures are directly accounted for in a company’s efforts to abate all of its supply chain emissions as it pursues its net-zero targets. In its September 2022 Forest, Land and Agriculture (FLAG) sector guidance, the SBTi accepts removals within a company’s supply chain towards greenhouse gas emission reduction targets.

On top of that, resources such as the Value Change program led by Gold Standard and the GHG Protocol’s Land Sector and Removals Guidance draft provide further guidance on how to account for the impacts of insetting interventions.

Some companies decide to implement negative emission initiatives into their supply chains

Wary about the quality concerns of carbon credits for sale on the open market, various firms have sought to develop their own initiatives. Philip Morris, Burberry, Accor, Nestlé, and PepsiCo are among the companies that have adopted insetting for emissions reductions or removals. So far, this has been primarily suited to companies with a focus on land use, such as food and beverage companies. These entities can leverage their networks of farmers and wider land-use capabilities to fund afforestation, reforestation, or sustainable agriculture activities within their value chain. As such, insetting efforts tend to focus on nature-based solutions, such as Nestlé’s efforts to plant millions of trees around its coffee plantations.

As admitted by IPI, “insetting currently does not require verification or certification against agreed global standards.” Due to the lack of detailed public documentation and third-party verification, the transparency and accountability of these programs are still ambiguous. As pointed out in a recent article by Mongabay, these processes often lack independent oversight, uniform high standards, and scientific rigor.

It is important to disentangle this from a similar trend that is happening in parallel: companies setting up their own carbon credit projects outside their value chain. This often involves partnering with, investing in, or acquiring project developers. For example, GSK invests in community-led projects that aim to restore 2,500 hectares of mangroves in Indonesia, while Shell's nature-based solutions team develops global projects. Orsted, Bayer, and Chevron have comparable efforts outside of their value chains running.

Options are increasing: The growing role of new technologies for insetting

In the past, options for insetting were limited, and it has so far mainly focussed on low-touch nature-based removal for companies with supply chains in the FLAG sector. However, with recent advances in technological carbon dioxide removal (CDR), the window of opportunity has widened. Companies can now implement direct air capture (DAC) units to their cooling towers, apply biochar as a soil amendment for crops, or use carbon-negative concrete in the construction of offices.

For instance, Novocarbo argues that the emerging biochar economy stands to play a major role in facilitating the shift from offsetting to insetting across industries. Building and utilizing carbon-negative pyrolysis plants allow different industries to capture carbon and avoid emissions through the sequestration of these carbon emissions, which are then subsequently turned into biochar.

Another prominent example of a novel way of doing insetting relates to the aviation sector’s use of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) – a cleaner substitute for traditional jet fuel. For this, the Smart Freight Centre and MIT Center for Transportation & Logistics already launched the “GHG accounting and insetting guidelines for sustainable aviation fuel” in 2021 to facilitate the use of more SAF and help decarbonize the sector. Although this insetting approach has its limitations, companies could address Scope 3 emissions from aviation by supporting the production and use of this more sustainable alternative jet fuel.

Indeed, the availability of new technological solutions is increasing, and they are becoming more accessible. With the introduction of new processes and industrial applications, the utilization of such technologies is likely to expand even further. However, one issue is that companies implementing an insetting approach may not pursue independent measurement and verification of their efforts. As the insetting interventions are not meant to generate carbon credits, standards, registries, and third-party verifications are usually sidelined. Without the mandate for additionality and permanence considerations, companies are free to devise their own quantification methodology.

To establish credibility for claims of carbon emissions elimination, an independent view is essential. This can partly be accomplished through proper monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) technology, but most of these services are still in the early stages of development. To make informed decisions about whether to “make or buy” and to better understand the overall decarbonization risk, it is paramount to ensure that data from a company’s insetting projects can be compared to VCM credits.

Insetting is imperfect but can be a valuable addition to a carbon credit portfolio if managed with full rigor

The emerging trend of companies embedding emissions reduction or removal activities within their own supply chain to meet decarbonization targets could further complicate the already complex VCM. In all the above examples, companies become both buyers and suppliers – a risky situation. Without the principal-agent relationship of buying credits from a third party, it is tricky to assure there is an independent view on quality.

Nevertheless, implementing insetting interventions may be a worthwhile pursuit for companies with supply chains that offer the potential to capture carbon. In those cases, insetting can be a valuable addition to a credit portfolio. To scale models of carbon insetting, it is crucial to generate multiple use cases that have been verified by third-party sources, establish a collaborative framework, and create a network for sharing best practices and program results.

It is crucial that companies keep a harmonized overview of their within- and beyond-supply chain measures. When mapping out a pathway to achieving net-zero, a consistent approach to evaluating quality dimensions and data points of both insetting and carbon credits is necessary to proactively manage risks to fall short. As such, insetting can be used to balance VCM shortfalls within the portfolio, and conversely, external carbon credits can be utilized to balance shortfalls related to insetting projects.

CEEZER supports such a balanced approach and allows companies to monitor negative emissions from insetting interventions together with their external carbon credits in a single portfolio. Combined portfolios allow keeping a clear view of within-supply-chain and beyond-supply-chain activities in a single, verified environment. That way, shortfalls from the one can be recovered by the other, and planning for-net zero becomes a whole lot easier.

To learn more about CEEZER, please get in touch or book a demo today.

%202-1.jpg)

.jpg)